Examples of Literature Review for Nutrition on Healthy Eating Habits

- Review

- Open Access

- Published:

A systematic review of types of healthy eating interventions in preschools

Nutrition Journal volume thirteen, Commodity number:56 (2014) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

With the worldwide levels of obesity new venues for promotion of healthy eating habits are necessary. Because children's eating habits are founded during their preschool years early educational establishments are a promising identify for making health promoting interventions.

Methods

This systematic review evaluates unlike types of healthy eating interventions attempting to foreclose obesity among iii to 6 year-olds in preschools, kindergartens and 24-hour interval care facilities. Studies that included unmarried interventions, educational interventions and/or multicomponent interventions were eligible for review. Included studies likewise had to have conducted both baseline and follow-up measurements.

A systematic search of the databases Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL and PubMed was conducted to place articles that met the inclusion criteria. The bibliographies of identified articles were also searched for relevant articles.

Results

The review identified 4186 manufactures, of which 26 studies met the inclusion criteria. Fifteen of the interventions took place in preschools, ten in kindergartens and one in another facility where children were cared for by individuals other than their parents. Seventeen of the 26 included studies were located in North America, 1 in S America, 5 in Asia, and 3 in a European context.

Healthy eating interventions in day care facilities increased fruit and vegetable consumption and nutrition related knowledge amid the target groups. Merely 2 studies reported a pregnant decrease in torso mass index.

Conclusions

This review highlights the scarcity of properly designed good for you eating interventions using articulate indicators and verifiable outcomes. The potential of preschools as a potential setting for influencing children's nutrient pick at an early on age should be more than widely recognised and utilised.

Introduction

The worldwide prevalence of overweight and obesity amid preschool children has increased from 4.ii% (95% CI: three.two%, five.2%) in 1990 to 6.7% (95% CI: v.six% – vii.7%) in 2010 and is expected to increase even further to 9.1% (95% CI: 7.3 – 10.9) in 2020 [1]. This increase is disturbing due to the accompanying social, psychological and wellness effects and the link to subsequent morbidity and bloodshed in machismo [two, iii].

Considering the consequences of overweight and obesity on both a personal and societal level, healthier eating habits among children should be promoted as one of the actions to prevent overweight and obesity in hereafter generations. The almost common place for health promotion amidst children has previously been in the school setting by and large with children aged 6 to 12 years-old. But, there are promising findings in interventions targeting infants and 5-year-olds, although there is an underrepresentation of interventions and research inside this historic period group [four]. Most of these interventions accept been taking identify in early pedagogy establishments for iii–half-dozen year-olds like preschools in the U.S. or kindergartens as they are chosen outside the U.S. as well equally daycare facilities, where children are nursed by a childcare giver in a individual home. In this setting children eat a large number of their meals and may consume upwardly to seventy% of their daily nutrient intake [5]. These captive settings present a venue for intervention because institutional catering may be designed in such a way that nutritional guidelines are followed, resulting in an acceptable food intake [6] and improved nutrient choices later in life [7]. The objectives of the early educational establishments are often to teach and develop the child's opportunities and skills that volition prepare them for a better future [8] and many of the previous interventions have either focused on developing food preferences among children often by exposure or with nutritional educational interventions or with a combination of these 2 approaches. Previous reviews take included intervention studies that evaluated the outcomes of dietary educational interventions versus control on changes in BMI, prevalence of obesity, rate of weight gain and other outcomes like reduction in body fat, only every bit stated previously this did not yield a sufficient number of studies to provide recommendations for practice [4, 9]. The Toybox study [10] has published a number of reviews about several aspects of wellness promotion efforts for pre-schoolers including the assessments tools of free energy-related behaviours used in European obesity prevention strategies [11], the effective behavioural models and behaviour change strategies underpinning preschool and school-based prevention interventions aimed at 4-6-year-olds [12]. They also published a narrative review of psychological and educational strategies applied to young children'southward eating behaviour in order to reduce the risk of obesity and constitute that there was potential for exposure and rewards studies to ameliorate children'due south eating habits [thirteen]. None of the recent published studies accept included both interventions that include both exposure or meal modification and educational interventions and multicomponent interventions that combine both approaches. With the exception of [thirteen] all the previous reviews include concrete activity and although this is an of import factor in obesity prevention, many interventions do but focus on nutritional education and is as such excluded from previous reviews.

The objective of this article is to review published literature on healthy eating interventions in 24-hour interval care facilities and analyse the effectiveness of unlike strategies in relation to their influence on children'due south nutrient option at an early age. Based on findings, this article as well provides recommendations for future interventions.

Methods

A systematic search for literature using four databases (PubMed, Scopus, Spider web of Scientific discipline and CINAHL) was carried out. The search strategy was based on a careful choice of keywords and clear, pre-established criteria for inclusion of studies.

Inclusion criteria

Included studies were intervention studies with the objective of treating or preventing the occurrence of obesity by influencing preschool children's eating habits. As a prerequisite for inclusion, the healthy eating interventions had to have place in institutions and had to take taken both baseline and follow-up measurements. Although it is best-selling that physical activity interventions are important and should not be disregarded, this study focuses solely on healthy eating interventions. Simply studies targeting children anile iii to 6 years were included as it is this age group that predominantly attends early pedagogy facilities. Since early on pedagogy and school systems vary from country to land, information technology was decided to include all interventions in day intendance facilities if the mean age was between 3 to six years sometime. Children in included studies likewise had to exist healthy at initial baseline measurement, although obese children were included in order to recognize the already existing prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and the necessity to acknowledge treatment of this particular target grouping. Interventions that focused on diet, nutrition, nutrient, eating or meals in twenty-four hour period care facilities were included. Due to the importance of environmental factors in children'southward acquirement of healthy eating habits, interventions including kitchen employees and childcare givers in day care facilities were also included. As the review concerns itself with the effectiveness of unlike interventional strategies, the types of interventions were categorized into single component interventions, educational components, and multicomponent interventions that aiming to promote good for you eating habits and counteract obesogenic actions in children attending day care facilities.

The review included studies measuring biological, anthropometric and attitudinal outcomes: torso mass alphabetize, z-scores for elevation and weight, waist to acme measurements, serum cholesterol levels, peel-fold measurements or prevalence of overweight and obesity in the sample population, as well as food consumption patterns, knowledge and mental attitude towards foods and liking and willingness to attempt new food.

Exclusion criteria

Research into weight loss of obese children and any interventions involving children with special needs or who were chronically ill and required on-going counselling, such as patients with diabetes or center disease, were excluded from the review. Studies taking place in plant nursery, primary or elementary schools were also excluded when the hateful historic period was either younger than 3 years or older than vi years old. Interventions targeting parents of preschool children and descriptive articles about pre-schoolers behaviour, noesis and consumption were also excluded. Lastly, studies including a concrete activity component were excluded unless the dietary component was clearly separated from the concrete activity intervention during implementation and assay.

Conducting the search

Literature for the review was obtained using a systematic search conducted during spring 2014 with relevant literature published upward to and including the search catamenia. A meta-assay was intended, however due to a lack of sufficient information, a meta-analytical comparison was difficult to deploy.

Databases

The databases Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL and PubMed databases were used for the literature search. The search was restricted to articles written in English, High german, Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish as these were the language capabilities present in the reviewing group. The filter for inquiry involving humans only was activated and the search was conducted to obtain manufactures published betwixt 1980 and 2014.

The search strategy was created using relevant terms describing settings, possible inputs in an intervention and possible outputs of an intervention. The search terms were refined a number of times in order to optimize the selection of manufactures, without compromising with the sensitivity of the search in order to take into account the vast number of articles published on the topic of children and obesity. The keywords tin can be found in Table 1.

Information management

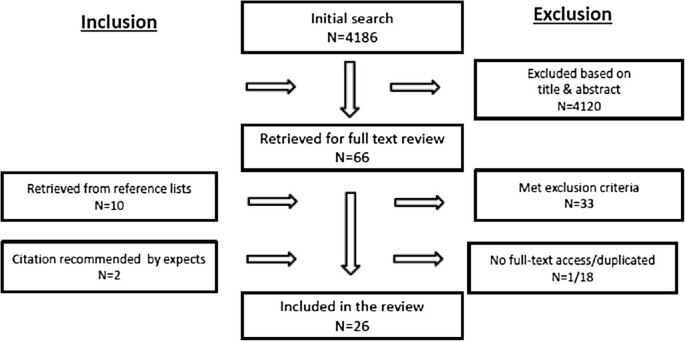

The search hits were downloaded and saved in the databases. A total of 4186 papers were identified and screened on the ground of titles and abstracts past the first author, who has experience within a preschool venue, leaving 66 papers for farther enquiries. Reference lists from the systematic review were scanned in order to identify interventions in kindergartens and preschools that the previous search had been unable to find. Altogether, ten papers were identified. Subsequently removing repeated studies and articles, 47 total text papers were retrieved through the library service at University of Aalborg, campus Copenhagen.The 47 remaining papers were read independently by three reviewers in social club to verify that they met the inclusion criteria. 33 papers were excluded equally a issue primarily because they did non publish results, solely was targeted parents or were descriptive in nature. The reviewing procedure resulted in 26 papers left for assay. Figure 1 contains an overview of the search process.

Flowchart of the written report selection process.

Data collection and analysis

Pick of studies

Articles identified in the literature search were read by the first author and divided between three reviewers for further evaluation and was debated in meetings with all 3 reviewers nowadays.

For each of the located interventions, the post-obit was extracted: aim of the report, setting where 3–6 year-olds were cared for by others than their parents, study design, characteristics of the target group, sampling methods, sample size, ethnicity, and theoretical background. Furthermore; duration, content and delivery mechanism of the intervention was extracted, as well as data well-nigh the command grouping, random allocation to control or treatment and whether there was information missing from the article.

Quality assessment

The quality of the identified studies was assessed using a rating scheme from * (weak) to **** (very potent). The studies were rated co-ordinate to the level of information bachelor, written report design, risk of bias, written report population and study duration. The quality rating scheme was adapted from the Cochrane guidelines on quality assessment [14]. Table 2 illustrates definition and explanation of the enquiry design rating scheme. Each included written report was rated independently amongst the 3 start authors (MVM, SH & LRS) with potent inter-rater reliability and disputes over assessment were settled through give-and-take.

Results

The 26 studies that the literature search resulted in were divided into 8 single intervention studies, 11 educational interventions and seven multicomponent studies. The unmarried intervention studies involved the modification of a single gene in the environment in order to promote fruit or vegetable intake and preferences in children. Educational interventions were carried out in the kindergartens, either by teachers that had undergone a instruction program or by nutritional educators provided by the inquiry program and aiming to increase children's knowledge of healthy eating. Multicomponent interventions included more than 1 strategy to influence eating behaviour.

Table three shows the characteristics of the studies.

Populations studied

Birthday, 17 of the 26 included studies were North American, iii of the studies were carried out in Asia, five in a European context and one report was conducted in South America. Thirteen of the interventions took place in preschools, 10 in kindergartens and iii in other facilities where 3 to half-dozen year-olds were cared for by others than their parents.

Ethnicity and socio-demographic characteristics of participants

The bulk of the unmarried interventions was from the Usa and included Caucasians. The educational interventions did non present a clear picture of any tendencies. All of the American multicomponent interventions were targeted towards low-income families or families from African-American or Latino backgrounds. The European interventions targeted children from middleclass families.

Interventions

Of the single intervention studies identified the majority [ten, 17–20, 22] made modifications to the serving of vegetables, serving either novel or non-preferred vegetables and looked at the upshot on vegetable preferences also as whether peer-models had an influence on the children's intake during dejeuner.

We identified eleven interventions consisting of nutritional educational programs carried out either by teachers in the kindergarten, individuals that had undergone a training program or past nutritional educators provided by the research project.

Seven multicomponent interventions included educational activities for the children and delivered similarly to the educational activities described previously. The multicomponent interventions as well encompassed other activities like availability of fresh water and fruits and in some cases vegetables [eight, 36, 39] the children participation in growing their own vegetables [22, 37], newsletters for parents [36, 41], food modifications in the canteen[42] and healthy school policies [41]. A detailed description of the interventions tin be found in Table 3.

Tabular array iv shows the quality cess and outcomes of interventions.

The written report design of included studies

Fourteen of the 26 studies included in this review were randomized controlled studies or cluster randomized controlled trials. Nine quasi-experimental designed studies were establish primarily as single or educational intervention [20–23, 29, 32–34, 42]. Just one study used a crossover design as command [19], just neither the sampling method nor the fourth dimension betwixt intervention and command were stated, making the control issue express.

Sampling methods

Random sampling had been used in only v of the 26 studies as almost of the studies were based on convenience sampling. Two studies combined random and convenience sampling [22, 34]. 4 studies did not draw the sampling method used [19, 23, 30, 31, 35].

Sample size

Sample sizes varied profoundly between single interventions and the educational and multicomponent interventions. The mean sample size of the single component interventions was 78 and the mean sample size among the educational and multicomponent interventions were 1031 and 522. The mean sample size of all 26 studies was 601.

Master target behaviours

Nutrient preferences, willingness-to-try novel foods and nutrient intake during dejeuner were the most used target behaviours in the single interventions. Not surprisingly knowledge and attitudes were the most used target behaviours in the educational interventions, but also consumption of target foods were evaluated using food frequency questionnaires answered by parents. The consumption of target foods were also evaluated in multicomponent studies, merely here the intake was measured using observation by researchers or teachers in the setting, simply every bit it was the case for unmarried interventions. Anthropometric measurements of elevation and weight were practical beyond the studies, although they just happened in two single interventions [19, twenty], however it was only used to control for BMI in the statistical analysis. The multicomponent interventions included other anthropometric measures besides.

Duration of intervention

The single change interventions were relatively short in duration, lasting from 3 to four days and up to six weeks. The educational interventions with a smaller sample size lasted from 5 to 8 weeks and the studies involving a higher number of participants were of longer duration of between 10 months to 2 years. Still, at that place were exceptions to this, including Cason [25] who evaluated a preschool nutrition program involving 6102 children over 24 weeks and Package et al., [32] who carried out a 4 year written report targeting approximately 200 preschool children Hendy [twenty] failed to report their intervention duration. The duration of the multicomponent interventions was generally between 4 and 7 months and up to 1 yr.

Theoretical foundations of interventions

16 of the 26 included interventions did not base their interventions on health behavioural theories. 6 of the studies used Bandura's social cognitive theory or the related social learning theory. Piaget's developmental theory was used in 2 studies and others were the theory of multiple intelligences or Zajonc's exposure theory.

Data missing from articles

In the unmarried interventions Hendy [20] failed to state the duration of their intervention and Ramsey et al. [23] did not mention their allocation procedure, however this was due to the written report taking place at ane canteen without private data. Nemet et al. [thirty] and Witt et al. [35] failed to study their sampling process, which was quite surprising because the high research rigour their studies otherwise presented.

Bias

The unmarried interventions generally had pocket-sized sample sizes, lacked controls and were of relatively brusk duration and with a brusque period of time in-between the exposure and follow-up measurements and. The majority of studies in both the educational and multicomponent intervention groups suffered from low response rates.

Furnishings of interventions

Single intervention

Single exposure interventions failed to demonstrate a significant increase in vegetable consumption. Fruit intake was more easily influenced, all the same. Results also showed that younger children in particular were influenced by role models and that girls may be more than promising role models than boys [17, 18].

Educational intervention

None of the educational interventions resulted in a change in anthropometric measurements, with the exception of [30] who observed a significant decrease in children'south BMI in the overweight children grouping who became normal weight. At follow-upwardly after 1 yr the BMI and BMI percentiles were significantly lower in the intervention grouping compared to the control grouping. Promising results were also plant in half dozen of the studies where an increase in the consumption of fruit and vegetables was observed. All the same, none of these changes were significant at the 0.05 level, with the exception of [35], where a significant increment was found in the consumption of fruit by 20.8% and in vegetable snacks by 33.1%. Witt et al. [35] found a pregnant increase in vegetables served outside preschools, but this was based on female parent's ain food frequency data, which may have biased the results [33]. One of the major effects of the educational interventions was in the level of knowledge among its participants. For instance, the level of nutrition-related knowledge increased in two studies [24, 30] and the identification of fruits and vegetables increased in 2 studies [25, 27].

Multicomponent interventions

Vi of the multicomponent interventions showed a significant increase in fruit and vegetable consumption, simply one institute the issue but to exist present on fruit consumption afterward follow-up after ane twelvemonth. None of the other studies constitute an effect on BMI, but ane intervention resulted in a decrease in the relative adventure of serum cholesterol among children [42]. Only one study [39] evaluated knowledge and found that familiarity with novel foods increased significantly.

Discussion and conclusions

This review finds that healthy eating interventions tin can influence the consumption of vegetables through different strategies. The studies acknowledged that a unmarried exposure strategy was bereft to increase vegetable consumption and that there needs to be an education component as well. This was supported past the fact that the over half of the educational interventions and six of the eight multicomponent interventions resulted in an increase in vegetable consumption. The increment in consumption was greater in the multicomponent studies which could point that the more comprehensive the intervention strategy, the more probable the intervention is to exist successful.

The effectiveness of the interventions on anthropometric change was more inconclusive, the unmarried interventions did not include measures of BMI and considering how brusk the duration of their interventions were, it might likewise be difficult to find change in anthropometric measures. None of the other intervention types that did in fact utilize anthropometric measurements institute an effect on BMI, with the exception of [31]. However Witt et al. [35] found an effect on serum cholesterol.

The educational and the majority of multicomponent interventions included an educational component and the sometime did find meaning increases in diet related knowledge, simply the multicomponent interventions did not evaluate intermediate effects of noesis in addition to anthropometrics. This highlights the fact that multicomponent interventions should include measures on knowledge, when they include an educational component, peculiarly, because the duration of multicomponent interventions ofttimes was shorter than the pure educational interventions and anthropometric alter is difficult to notice during short intervention periods. A lack of follow-upwardly in all of the interventions makes it hard to conclude whether the observed furnishings were sustainable over time. With the exception of De Bock et al. [38] and Hoffman et al. [twoscore] the multicomponent and even some of the educational intervention failed either to base of operations or mention the theoretical foundations that they based their educational programmes on. This may exist excused in the single interventions that base their studies on empirical information from food choice development theories, only interventions aiming at delivering educational programmes should take some knowledge of wellness behavioural or educational theories that explains the process backside the success or failure of the implementation of their educational programs. This is once again highlighted by the fact that procedure evaluations were merely performed in three of the interventions and the evaluations consisted of either revision of the provided educational materials or checking the adherence to the programme, but they did non focus on drivers or barriers backside the implementation of the interventions and thereby to increment the understanding of what made the intervention successful or unsuccessful.

Ethnicity and socio-demographic background play an important role in the evolution of eating habits and this should exist taken into account so interventions are targeted towards those that need it the most. A setting-based approach tin can exist an of import intermediate for this, if information technology is practical to institutions where children of low-income families are nursed and educated. Several educational and multicomponent interventions were targeted towards institutions with children of depression-income families and several of them e.g. Cespedes et al. [26], Vereecken et al. [41], and Williams et al. [42] had positive results especially on the consumption of fruits and vegetables that supports the notion of early education establishments as a potential setting to decrease inequalities in wellness.

Quality of the show

Overall the quality of the intervention studies became better the more comprehensive they were; the unmarried intervention studies were generally of weak quality with small sample sizes, curt durations and, in some cases, a lack of controls, which makes it difficult to generalize to a larger population, especially because they were mostly carried out among American Caucasians from families with high socio-economic status. The educational interventions were of better quality and with the largest populations, simply yet suffered from limitations similar lack of consideration in the allocation process, in some cases lack of controls and high drop-out rates. The multicomponent interventions were the most well-designed studies, simply also suffered from high drib-out rates and as mentioned higher up the effectiveness of the educational components were difficult conclude upon, because they failed to evaluate on knowledge. With the exception of Nemet et al. [31] in that location was a lack of follow-up evaluations that makes it difficult to state whether the outcomes of interventions are sustainable over time.

Author'southward conclusions

Implications for practice

The majority of interventions plant promising results when targeting the consumption of salubrious foods or when attempting to increment children'due south knowledge of healthy eating, providing sufficient evidence in support of using preschools as a setting for the prevention of chronic disease by making behavioural and lifestyle changes. Interventions are more probable to be successful if they take actions on several levels into account.

Implications for enquiry

This review supports the need for a longer follow-up of intervention studies in guild to assess whether results will be sustainable and how they might influence children'south eating habits subsequently in life. Anthropometric measurements were included in some of the multicomponent interventions just as nutritional status measured equally BMI does not change rapidly, interventions using BMI every bit the outcome measure should exist of a longer duration or they should include other intermediate measures such equally knowledge and consumption in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention.

Parents may not always be aware of what their children consume outside of the home, or about their knowledge surrounding fruits and vegetables, especially when children acquire near food and healthy eating behaviour in their kindergartens. Even though many choices are fabricated on behalf of the children by their parents at habitation, children today spend a reasonably large amount of fourth dimension abroad from the home surround in day care facilities, together with playmates or cared by other members of family. Equally a result, a child's nutrient choice is no longer restricted to being a sole family matter. Children'southward noesis and awareness of food is also being influenced in pedagogical activities, in day intendance facilities or by talking to their peers. It would therefore be suitable to develop innovative information drove methods, ensuring that the children are able to express what they similar to consume and what they know well-nigh a given food-related topic. Such innovative enquiry methods should take the developmental stages of the children into account and could perchance rely more heavily on pictures or on Information technology material.

The review found that healthy eating interventions in preschools could significantly increase fruit and vegetable consumption and nutrition-related cognition among pre-school children if the strategy used, is either educational or an educational in combination with supporting component. It further highlights the relative scarcity of properly designed interventions, with clear indicators and verifiable outcomes. Key messages are that preschools are a potentially of import setting for influencing children'due south food choice at an early age and that in that location is nevertheless room for enquiry in this field. Healthy eating promotion efforts have previously been focusing on schools, merely inside the last decade the focus have started to shift to pre-schoolers. This review synthesizes some of the interventions that promote healthy eating habits on early educational activity establishments using different strategies. The field of health promotion amongst this younger age group is yet in its before stages, but hereafter studies with thorough inquiry designs are currently existence undertaken like the Toybox study [10] and The Growing Health Report [43], the good for you caregivers-Good for you children [44] and the Program Si! [45]. These studies may improve our understanding of the effectiveness and underlying mechanisms backside successful implementation of salubrious eating efforts in early teaching establishments.

Highlights

-

Healthy eating interventions in preschools were classified by their type.

-

Comprehensive interventions were more than likely to succeed in behaviour alter, especially when targeting children of low-income families

-

Preschools are a promising venue for increasing fruit and vegetable consumption.

-

Evaluations showed a positive increase in food-related knowledge.

-

Properly designed interventions, with clear indicators and outcomes are deficient.

References

-

De Onis G, Blössner M, Borghi Eastward: Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010, 92 (5): 1257-1264.

-

Earth Health Organization: Milestones in Health Promotion: Statements from Global Conferences. 2009, Geneva: Globe Health Organization

-

Earth Health Arrangement: European Charter on Counteracting Obesity.WHO European Ministerial Conference on Counteracting Obesity, Istanbul, Turkey, fifteen–17 November 2006.Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2006, Copenhagen: WHO Regional Part for Europe

-

Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, Dark-brown T, Campbell KJ, Gao Y, Armstrong R, Prosser L, Summerbell CD: Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, 12: 00-

-

Mikkelsen Exist: Images of foodscapes: Introduction to foodscape studies and their application in the report of salubrious eating out-of-home environments. Perspect Public Wellness. 2011, 131 (5): 209-216.

-

Lehtisalo J, Erkkola M, Tapanainen H, Kronberg-Kippilä C, Veijola R, Knip M, Virtanen SM: Food consumption and nutrient intake in day care and at home in 3-yr-old Finnish children. Public Wellness Nutr. 2010, 13 (six): 957-

-

Schindler JM, Corbett D, Forestell CA: Assessing the effect of nutrient exposure on children's identification and acceptance of fruit and vegetables. Eating Behav. 2013, 14 (ane): 53-56.

-

Moss P: Workforce Issues in Early Babyhood Educational activity and Care. 2000, New York: Columbia University, New York

-

Bluford DA, Sherry B, Scanlon KS: Interventions to forestall or treat obesity in preschool children: a review of evaluated programs. Obesity. 2007, xv (6): 1356-1372.

-

ToyBox Study. [http://www.toybox-study.european union/?q=en/node/1] Terminal assesed June 17

-

Mouratidou T, Mesana M, Manios Y, Koletzko B, Chinapaw M, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Socha P, Iotova V, Moreno L: Assessment tools of energy residual‒related behaviours used in European obesity prevention strategies: review of studies during preschool. Obes Rev. 2012, 13 (s1): 42-55.

-

Nixon C, Moore H, Douthwaite Due west, Gibson E, Vogele C, Kreichauf S, Wildgruber A, Manios Y, Summerbell C: Identifying constructive behavioural models and behaviour change strategies underpinning preschool‒and school‒based obesity prevention interventions aimed at iv–6‒year‒olds: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2012, 13 (s1): 106-117.

-

Gibson EL, Kreichauf S, Wildgruber A, Vögele C, Summerbell C, Nixon C, Moore H, Douthwaite West, Manios Y: A narrative review of psychological and educational strategies practical to young children'due south eating behaviours aimed at reducing obesity adventure. Obes Rev. 2012, 13 (s1): 85-95.

-

Higgins JP, Green S: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series. 2008, Chichester, Uk: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

-

Seymour JD, Yaroch AL, Serdula M, Blanck HM, Khan LK: Impact of nutrition environmental interventions on point-of-purchase beliefs in adults: a review. Prev Med. 2004, 39: 108-136.

-

Bannon K, Schwartz MB: Bear on of diet messages on children's food choice: Pilot report. Ambition. 2006, 46 (2): 124-129.

-

Birch LL: Effects of peer models' food choices and eating behaviors on preschoolers' food preferences. Child Dev. 1980, 51 (2): 489-496.

-

O'Connell ML, Henderson KE, Luedicke J, Schwartz MB: Repeated exposure in a natural setting: A preschool intervention to increase vegetable consumption. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012, 112 (2): 230-234.

-

Harnack LJ, Oakes JM, French SA, Rydell SA, Farah FM, Taylor GL: Results from an experimental trial at a Head Start center to evaluate two repast service approaches to increase fruit and vegetable intake of preschool aged children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012, ix: 51-

-

Hendy H: Effectiveness of trained peer models to encourage food acceptance in preschool children. Appetite. 2002, 39 (3): 217-225.

-

Leahy KE, Birch LL, Rolls BJ: Reducing the energy density of an entree decreases children'due south energy intake at tiffin. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008, 108 (1): 41-48.

-

Noradilah One thousand, Zahara A: Credence of a test vegetable after repeated exposures among preschoolers. Malaysian J Nutr. 2012, eighteen (i): 67-75.

-

Ramsay S, Safaii Due south, Croschere T, Branen LJ, Wiest M: Kindergarteners' entrée intake increases when served a larger entrée portion in school lunch: a quasi‒experiment. J Sch Wellness. 2013, 83 (4): 239-242.

-

Başkale H, Bahar Z: Outcomes of diet noesis and healthy food choices in v‒to 6‒year‒old children who received a diet intervention based on Piaget's theory. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2011, xvi (four): 263-279.

-

Cason KL: Evaluation of a preschool nutrition education program based on the theory of multiple intelligences. J Nutr Educ. 2001, 33 (3): 161-164.

-

Céspedes J, Briceño G, Farkouh ME, Vedanthan R, Baxter J, Leal M, Boffetta P, Hunn G, Dennis R, Fuster V: Promotion of Cardiovascular Wellness in Preschool Children: 36-Month Cohort Follow-upward. Am J Med. 2013, 126 (12): 1122-1126.

-

Gorelick MC, Clark EA: Effects of a nutrition program on cognition of preschool children. J Nutr Educ. 1985, 17 (3): 88-92.

-

Hu C, Ye D, Li Y, Huang Y, Li L, Gao Y, Wang S: Evaluation of a kindergarten-based nutrition didactics intervention for pre-school children in China. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 13 (ii): 253-

-

Johnson SL: Improving Preschoolers' self-regulation of energy intake. Pediatrics. 2000, 106 (6): 1429-1435.

-

Nemet D, Geva D, Pantanowitz M, Igbaria N, Meckel Y, Eliakim A: Health promotion intervention in Arab-Israeli kindergarten children. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metabol. 2011, 24 (eleven–12): 1001-1007.

-

Nemet D, Geva D, Pantanowitz M, Igbaria North, Meckel Y, Eliakim A: Long term effects of a health promotion intervention in low socioeconomic Arab-Israeli kindergartens. BMC Pediatr. 2013, thirteen (1): 45-

-

Packet GS, Bruhn JG, Murray JL: Preschool wellness teaching program (PHEP): assay of educational and behavioral effect. Health Educ Behav. 1983, 10 (3–4): 149-172.

-

Piziak V: A pilot study of a pictorial bilingual nutrition didactics game to ameliorate the consumption of healthful foods in a caput start population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012, 9 (iv): 1319-1325.

-

Sirikulchayanonta C, Iedsee K, Shuaytong P, Srisorrachatr Due south: Using food feel, multimedia and role models for promoting fruit and vegetable consumption in Bangkok kindergarten children. Nutr Diet. 2010, 67 (2): 97-101.

-

Witt KE, Dunn C: Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption among preschoolers: evaluation of 'color me salubrious'. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012, 44 (2): 107-113.

-

Bayer O, von Kries R, Strauss A, Mitschek C, Toschke AM, Hose A, Koletzko BV: Brusque-and mid-term effects of a setting based prevention program to reduce obesity risk factors in children: a cluster-randomized trial. Clin Nutr. 2009, 28 (ii): 122-128.

-

Brouwer RJN, Neelon SEB: Scout Me Abound: A garden-based pilot intervention to increase vegetable and fruit intake in preschoolers. BMC Public Health. 2013, xiii (1): 1-6.

-

De Bock F, Breitenstein 50, Fischer JE: Positive bear on of a pre-school-based nutritional intervention on children's fruit and vegetable intake: results of a cluster-randomized trial. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 15 (03): 466-475.

-

Hammond GK, McCargar LJ, Barr S: Student and parent response to apply of an early childhood nutrition educational activity plan. Can J Diet Pract Res. 1998, 59 (3): 125-131.

-

Hoffman JA, Thompson DR, Franko DL, Power TJ, Leff SS, Stallings VA: Decaying behavioral effects in a randomized, multi-year fruit and vegetable intake intervention. Prev Med. 2011, 52 (v): 370-375.

-

Vereecken C, Huybrechts I, Van Houte H, Martens V, Wittebroodt I, Maes Fifty: Results from a dietary intervention study in preschools "Beastly Healthy at Schoolhouse". Int J Public Health. 2009, 54 (3): 142-149.

-

Williams CL, Strobino BA, Bollella M, Brotanek J: Cardiovascular adventure reduction in preschool children: the "Good for you Start" projection. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004, 23 (two): 117-123.

-

Miller AL, Horodynski MA, Herb HE, Peterson KE, Contreras D, Kaciroti N, Staples-Watson J, Lumeng JC: Enhancing self-regulation every bit a strategy for obesity prevention in Caput Start preschoolers: the growing healthy study. BMC Public Health. 2012, 12: 1040-doi:x.1186/1471-2458-12-1040.

-

Natale R, Scott SH, Messiah SE, Schrack MM, Uhlhorn SB, Delamater A: Pattern and methods for evaluating an early childhood obesity prevention program in the childcare middle setting. BMC Public Wellness. 2013, xiii (ane): 78-

-

Peñalvo JL, Santos-Beneit G, Sotos-Prieto M, Martínez R, Rodríguez C, Franco One thousand, López-Romero P, Pocock S, Redondo J, Fuster V: A cluster randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of a school-based behavioral intervention for wellness promotion amid children aged 3 to 5. BMC Public Health. 2013, 13 (1): 656-

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors were involved in the design of the review. MVM performed the literature search. MVM, SH, LRS read and rated the manufactures. MVM wrote the manuscript with the aid of SH, LRS and FJPC edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is published under license to BioMed Cardinal Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original piece of work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/ane.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this commodity

Mikkelsen, Thousand.V., Husby, S., Skov, Fifty.R. et al. A systematic review of types of healthy eating interventions in preschools. Nutr J 13, 56 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-56

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-56

Keywords

- Preschool

- Kindergarten

- Healthy eating

- Intervention

- Obesity

- Vegetable consumption

Source: https://nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2891-13-56

0 Response to "Examples of Literature Review for Nutrition on Healthy Eating Habits"

Post a Comment